(CNN) -- Curious about life on Mars? NASA's rover Curiosity has now given scientists the strongest evidence to date that the environment on the Red Planet could have supported life billions of years ago.

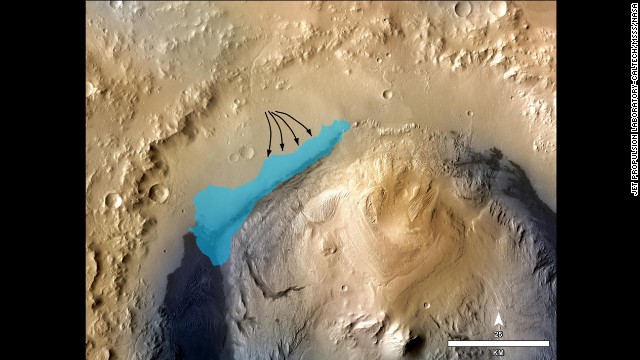

Since Curiosity made its rock star landing more than a year ago

at Gale Crater, the focal point of its mission, the roving laboratory

has collected evidence that gives new insights into Mars' past

environment.

NASA scientists announced in March that Mars could have once hosted life

-- at least, in the distant past, based on the chemical analysis of

powder collected from Curiosity's drill. An area of the crater known as

Yellowknife Bay once hosted "slightly salty liquid water," Michael

Meyer, lead scientist for the Mars Exploration Program at NASA

headquarters in Washington, said earlier this year.

Six new studies

released Monday by the journal Science add more insights about these

formerly habitable conditions and provide other new knowledge that

increase our understanding of the Red Planet. The results were also

presented at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San

Francisco.

Curiosity found evidence

of clay formations, or "mudstone," in Yellowstone Bay, scientists said

Monday. Martian mud is a big deal because this clay may have held the

key ingredients for life billions of years ago. It means a lake must

have existed in this area.

"This is a game changer

since these are the kind of materials that are very 'Earth-like' and

conducive for life," said Douglas Ming, lead author of one of the new

studies.

This ancient environment, where the clay minerals formed, would have been favorable to microbes, Ming told CNN.

Some bacteria on Earth

called chemolithoautotrophs could have lived in that kind of

environment. These bacteria derive their energy from breaking down rocks

and sediments, Ming said, generally by oxidizing elements in the rock.

Ming and colleagues also

found hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus in the

sedimentary rocks at Yellowknife Bay, elements that are all critical for

life.

The new findings mean

the rover's $2.5 billion mission is "turning the corner," said John

Grotzinger, a California Institute of Technology planetary geologist and

chief scientist for Curiosity, also known as the Mars Science

Laboratory.

Grotzinger and

colleagues found the habitable environment existed later in Martian

history than previously thought. By studying physical characteristics of

rock layers in and near Yellowknife Bay, they determined that Mars was

habitable less than 4 billion years ago -- about the same time as the

oldest signs we have for life on Earth.

The habitable conditions

could have remained for millions to tens of millions of years, with

rivers and lakes appearing and disappearing over time.

Curiosity also helped

scientists figure out the age of an ancient Martian rock, as described

in the new research. The rock is called Cumberland, and it now has the

distinction of being the first whose age was measured on another planet

through chemical analysis.

The rover used a method

for dating Earth rocks that measures the decay of an isotope of

potassium as it slowly changes into argon. Scientists determined the

rock was between 3.86 billion and 4.56 billion years old. This age range

is consistent with earlier estimates for rocks in Gale Crater.

Scientists say roughly 4

billion years ago, the environment on Mars wasn't much different from

that of modern-day Earth. But things on Mars then took a drastic turn,

and the planet was dramatically transformed from warm and wet to

bitterly cold and dry, scientists say. In addition to the cold and dry

conditions, scientists say the No. 1 reason life probably wouldn't have

thrived on Mars is its extremely high levels of radiation.

"The radiation

environment on Mars is unlike anything we have on Earth," said Jennifer

Eigenbrode, a biogeochemist and geologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight

Center and an author of one of the studies. "We don't know if life on

Mars could have ever adapted to the high levels of radiation the surface

is currently experiencing."

Eigenbrode added, "This is a wide-open book, which we have barely started writing the pages of."

New radiation measurements will also be important to planning any human missions to Mars, scientists said.

"Our measurements also

tie into Curiosity's investigations about habitability," study co-author

Don Hassler of Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said

in a statement. "The radiation sources that are concerns for human

health also affect microbial survival as well as preservation of organic

chemicals."

Organic chemicals come from a variety of sources, including meteorites and comets, but they can also be indicative of life.

What's bad for us is bad for signs of life -- but these organic chemicals could still be hiding on Mars nonetheless.